A special joint meeting of the AAS and the ICAS in celebration of 70 years of Asian Studies

(Honolulu, Hawaii 2011)

SESSION 194. The Printed Book as a Physical Object in Early Modern Japan, 1600-1900

日本近世期 (17〜19世紀)におけるモノとしての〈板本〉

(March 31 Thu. 7:00pm-9:00pm Room 321B)

Bookmakers and the Publishing Systems of Nineteenth-Century Japanese Fiction

造本から見る江戸読本の出板システムについて

TAKAGI, Gen (Professor of Chiba University)

高木 元 (千葉大学教授)

Abstract

This paper will focus on the production of commercial fiction in Japan

during the first half of the nineteenth century by focussing on the

process through which Kyokutei Bakin's great novel the Hakkenden was

produced and distributed. While the Hakkenden was produced as

commercial fiction, the books themselves were beautifully produced and

came, after their discovery by Western collectors, to be thought of as

works of art.

The focus of my talk will be the publishing process beginning with the

publisher who coordinated the work of the author and illustrator with

that of several craftsmen including the copyist, the block carver, and

the printer. While this process was in many ways shaped by the

Chinese model of book production going back to the Song, the bindings,

cover designs, and frontispieces used in this fiction were all

developed specifically for the commercial book market in Japan and

would continue to influence the look and feel of Japanese fiction well

into the Meiji period even after moveable type was widely adopted.

The talk will conclude with a discussion of the production and

circulation of various later and pirated editions, digests,

pornographic versions of the Hakkenden produced well into the Meiji

period as a way to sketch the social history of the book trade across

Japan's nineteenth century.

概 要

十九世紀日本文学を代表する長編稗史小説である『南総里見八犬伝』は、

〈江戸読本〉の典型でもあり、和紙に板木を用いて摺った〈板本〉として作成された。

特に、錦絵と同様に、〈彫り〉と〈摺り〉との高度な技巧が駆使された初摺本は、大変に美しく、

ほとんど〈手工芸品〉であるといっても差し支えない。

さて、これら板本が商品として生産されるプロセスにおいては、プロデューサーとしての板元が、

本の企画から始めて、作者や画工を含めた筆工や摺師など各職人を統括していた。

一方、江戸読本の造本を見ると、中国書籍の形態から影響を受けつつも、装丁や見返の意匠、

口絵挿絵などに大きな特徴がある。草双紙は勿論であるが、読本にあっても絵画意匠が大きな意味を持っていたのである。

とりわけ、後摺本や抄録本、艶本などの派生本、明治期の活字翻刻本に至るまで、

内容もさることながら造本的な側面での継承と変化が見られる。これらの興味深い現象について考えてみたい。

こんばんは、千葉大学の高木です。

Good evening. I am TAKAGI Gen of Chiba University.

残念ながら私は英語が使えないので、ミシガン大学のツィッカー氏をわずらわせて、発表原稿を英訳して貰いました。氏の協力に心より感謝します。勿論、発音も下手くそですから、もし何か分らないことがあれば、発表後に質問をして下さい。

My spoken English is limited so I have asked Professor Jonathan Zwicker of Michigan University to translate my paper into English and would like to thank him for his help. And I am afraid that my pronunciation may be difficult to understand at times so please feel free to ask questions during the Q&A period.

さて、私はこのささやかな発表を通じて、近年の日本国内外における日本文学(日本美術を含む)研究に見られる、少し気がかりな傾向に対して問題提起を行ってみたいと思っています。

Through my presentation today, I would like to try to problemetize what I see as a somewhat troubling trend within recent studies of Japanese literature - and art - both in Japan and abroad.

日本文学の研究史において〈テキスト論〉が提起した問題はとても大きかったと思います。しかし、それを乗り越えて、我々が新たな方法論を手にしたとは、必ずしも言いがたいのです。むしろ、学界全体の傾向としては、素朴に作者(絵師)を絶対化する、保守的な文芸批評や美術鑑賞的な研究方法に戻ってしまったようにすら思われます。そこで、〈モノとしての板本〉という物理的なメディアをめぐる実態について、その具体的な様子を紹介しつつ、作者の位置を相対化をしてみたいと思います。

Within the history of the study of Japanese literature, problems derived from textual studies have been extremely important. And yet it is not the case that we have necessarily, based on such studies, come to a new methodology. Rather it seems as if we have in some ways returned to a somewhat old-fashioned mode of literary criticism and artistic appreciation in the academy at large in which we often naively reify the author or (artist). Thus I would like to relativize the place of the author through and examination of historical conditions surrounding the block printed book as a thing - a medium materially embodied - and by giving specific examples.

まず、江戸時代における代表的な小説ジャンルである〈読本(よみほん)〉という〈絵入本〉の画像をご覧に入れます。

I would like to begin with some examples taken from a genre of illustrated books called “Yomihon” which are representative of the fiction of the Edo period.

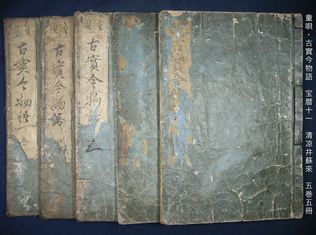

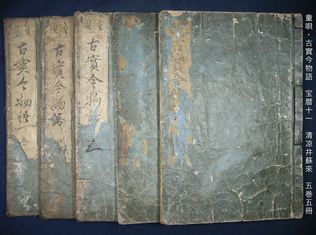

01.『童唄(わらべうた)・古実今物語(こじついまものがたり)』(清涼井蘇来作、宝暦十一〈1761〉年刊)

Warabe Uta: Kojitsu Imag Monogatari by Seiryousei Sorai, 1761

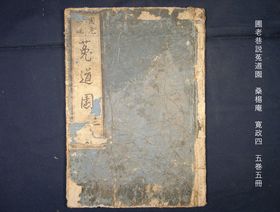

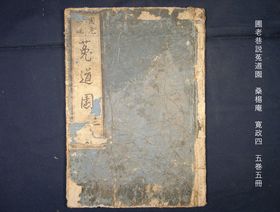

02.『圃老巷説菟道園(ほろうこうせつうじのみち)』(桑楊庵作、寛政四〈1792〉年刊)

Horoukousetsu Ujinosono by Souyouan, 1792

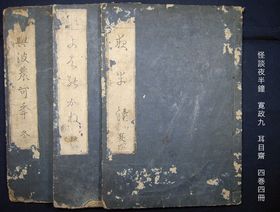

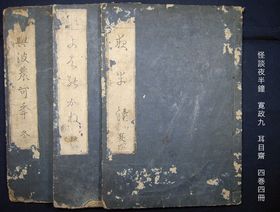

03.『怪談夜半鐘(かいだんよわのかね)(耳目斉作、寛政九〈1797〉年刊)』

Kaidan Yowanokane by Jimokusai, 1797

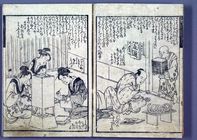

これらは十八世紀に出板されたもので、絵や模様の入っていない縹色の表紙に題簽を貼っただけの、とても地味なものです。挿絵も入っていますが、墨一色の略画でシンプルなものです。

These examples were published in the eighteenth century and have covers that are quite plain containing no patters or images but only bearing a “Daisen” on which the title is printed. These books do include illustrations but they are simple designs printed in black and white.

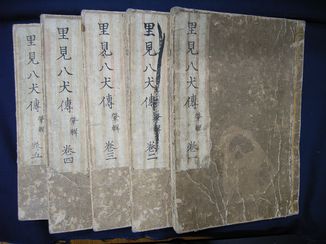

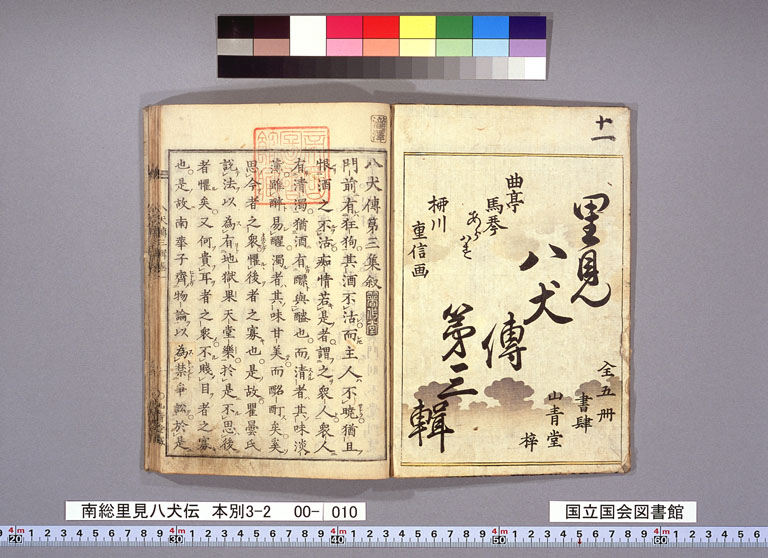

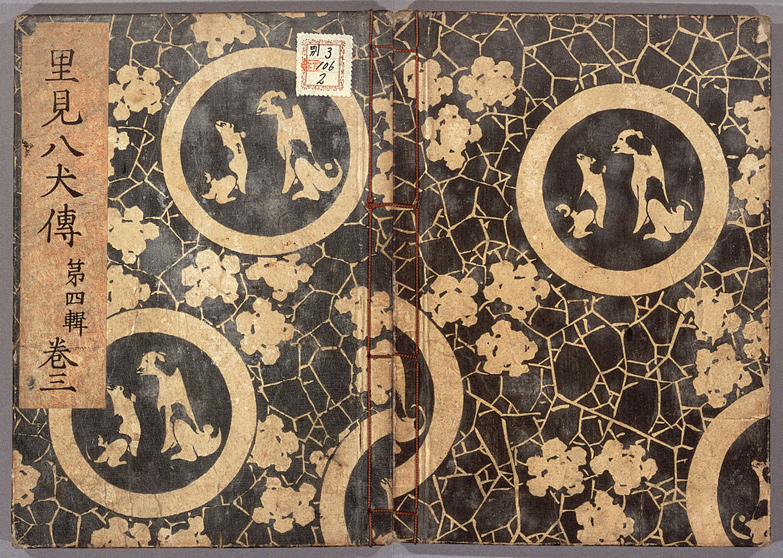

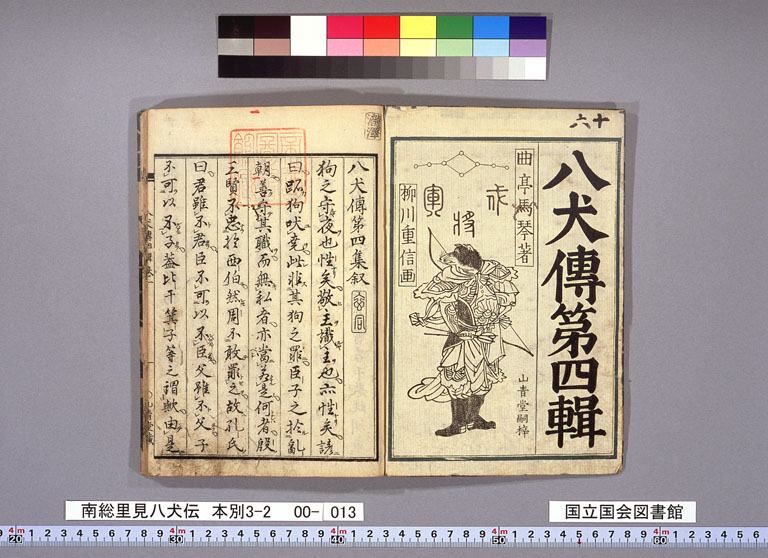

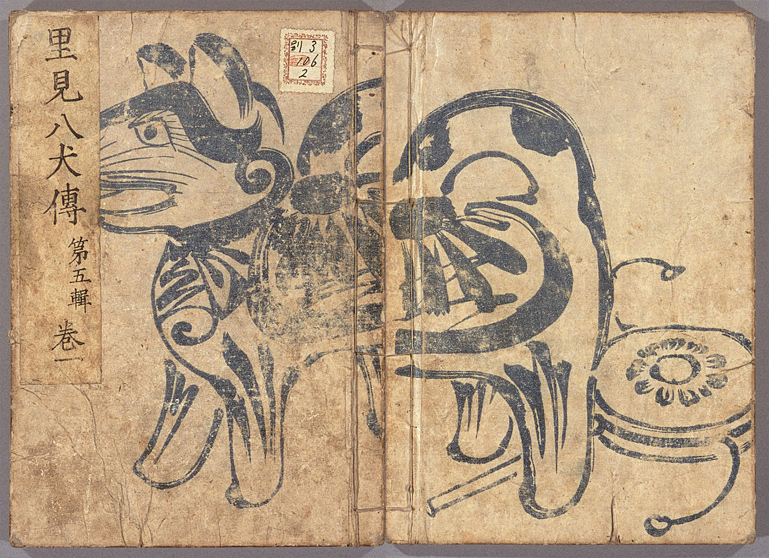

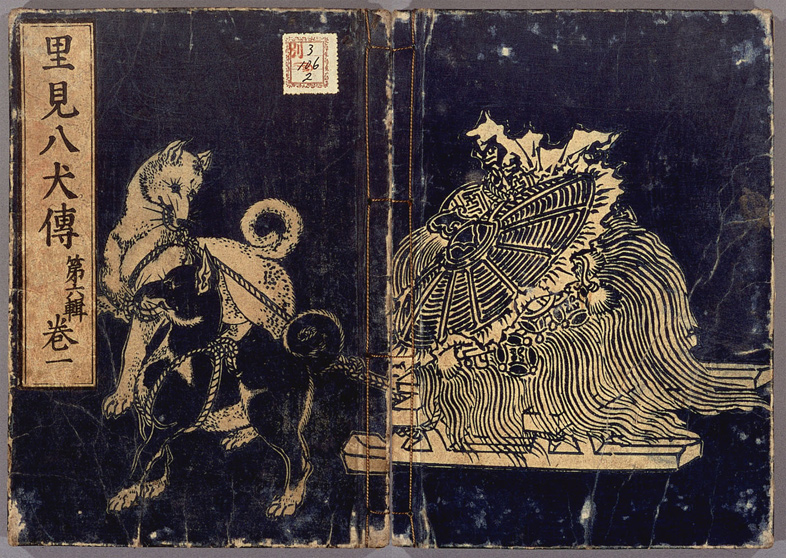

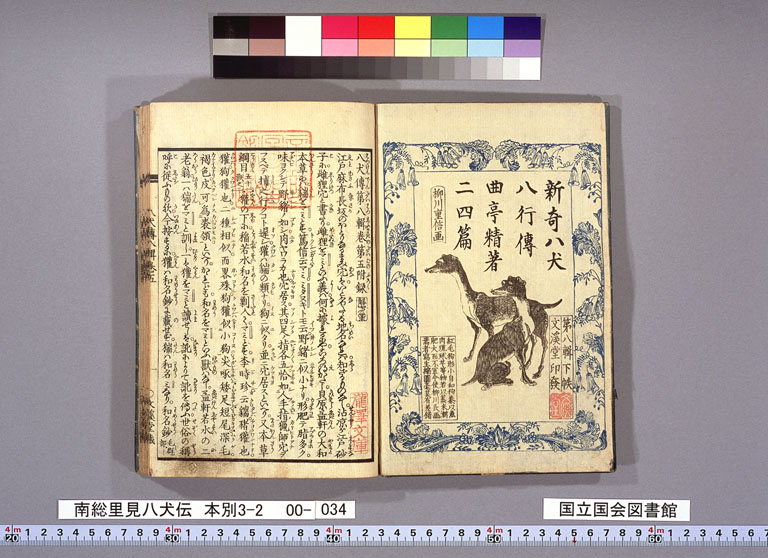

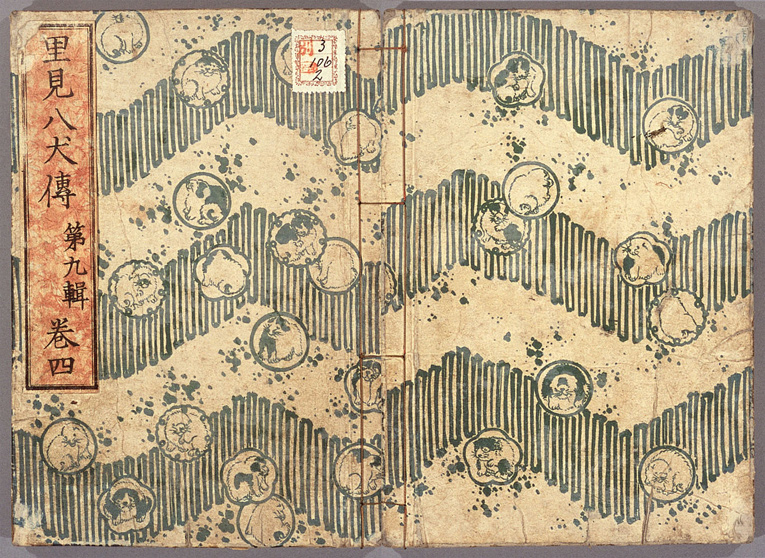

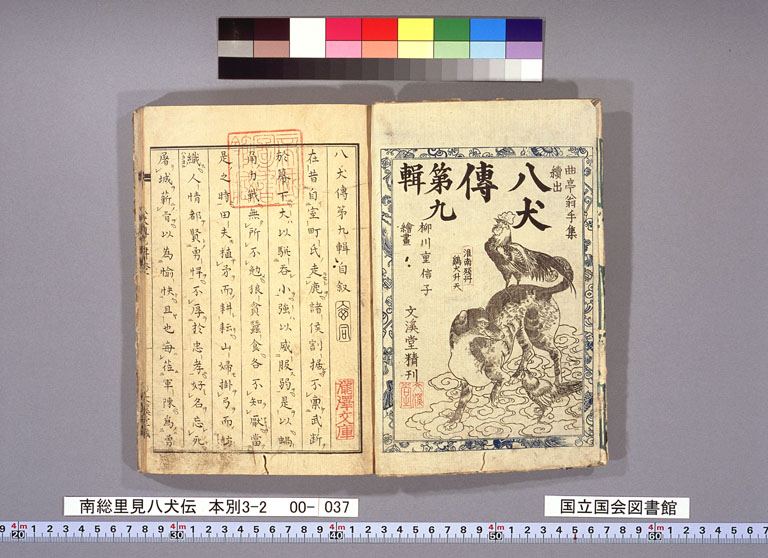

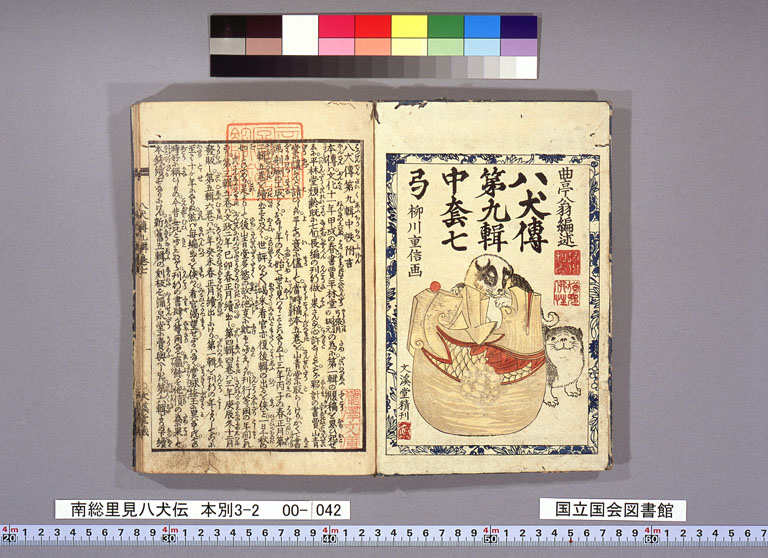

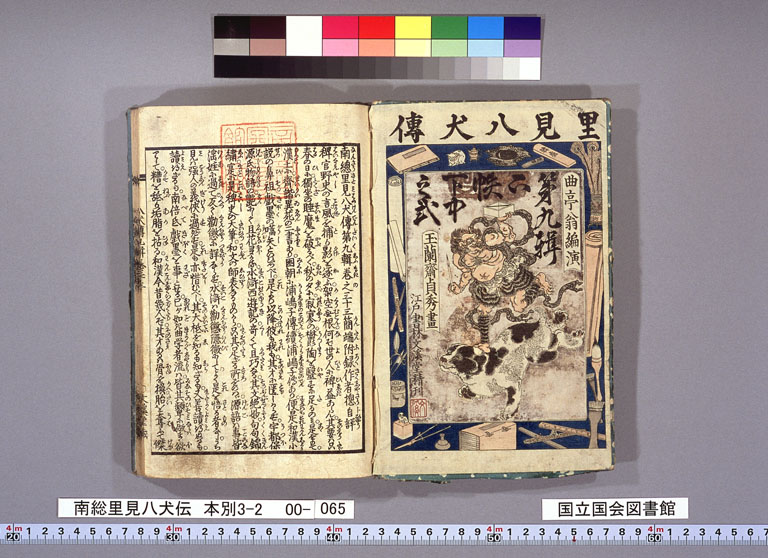

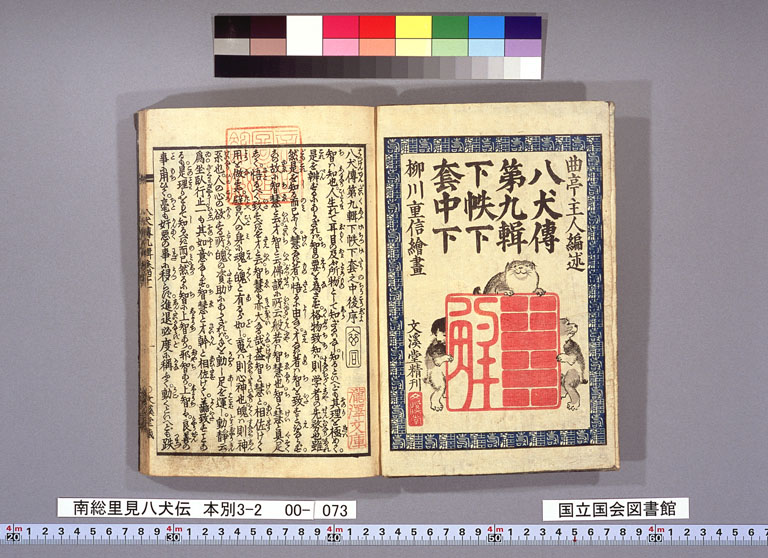

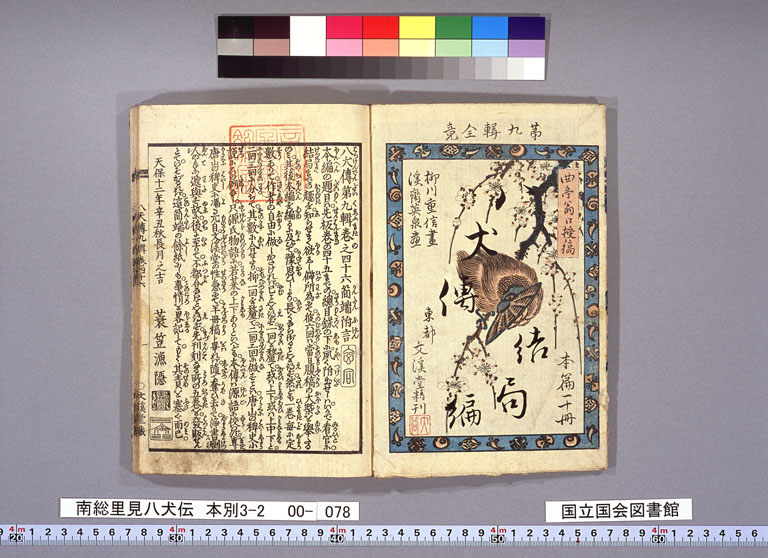

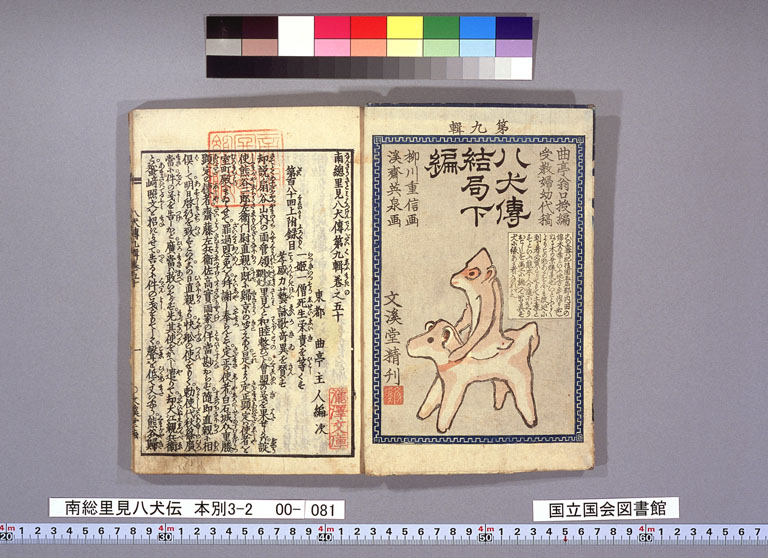

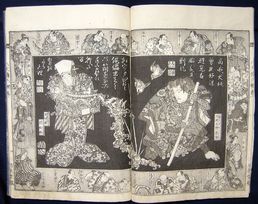

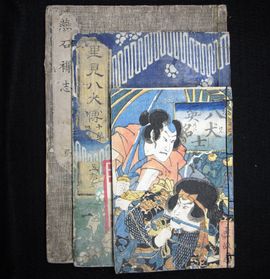

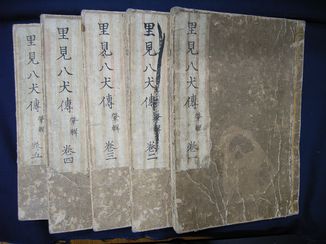

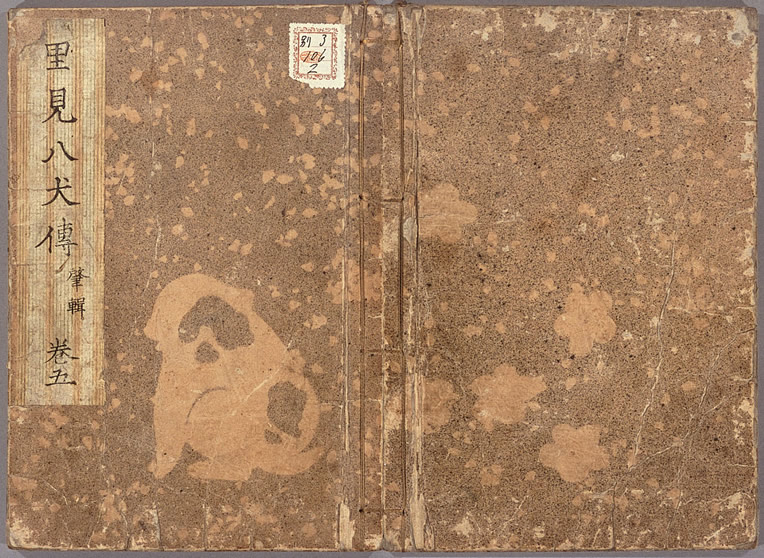

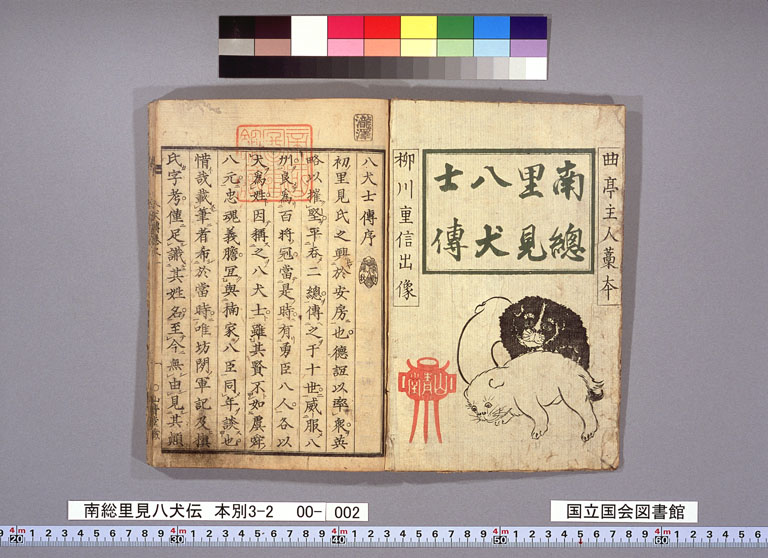

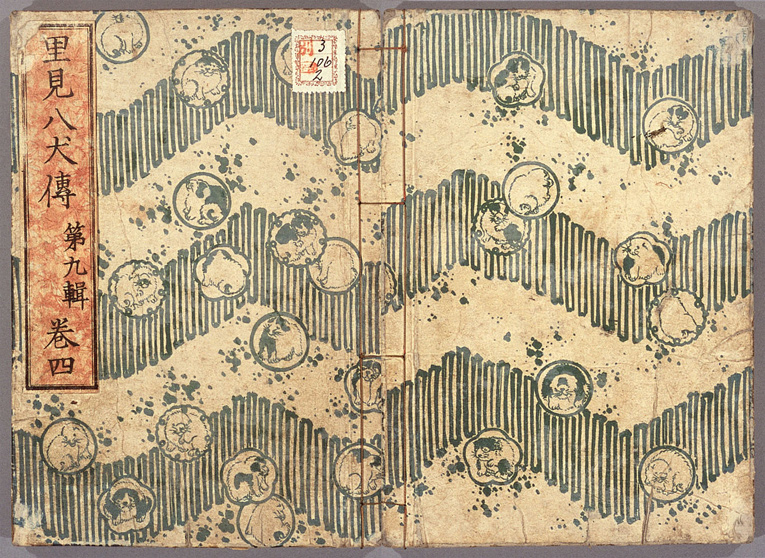

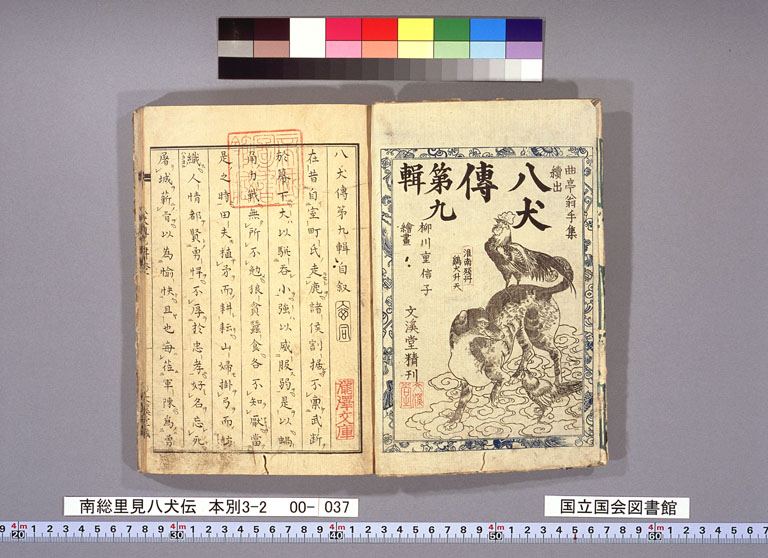

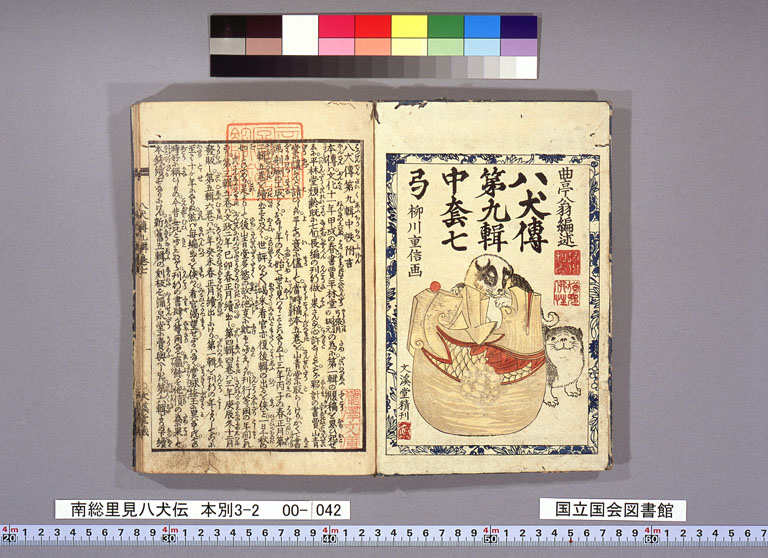

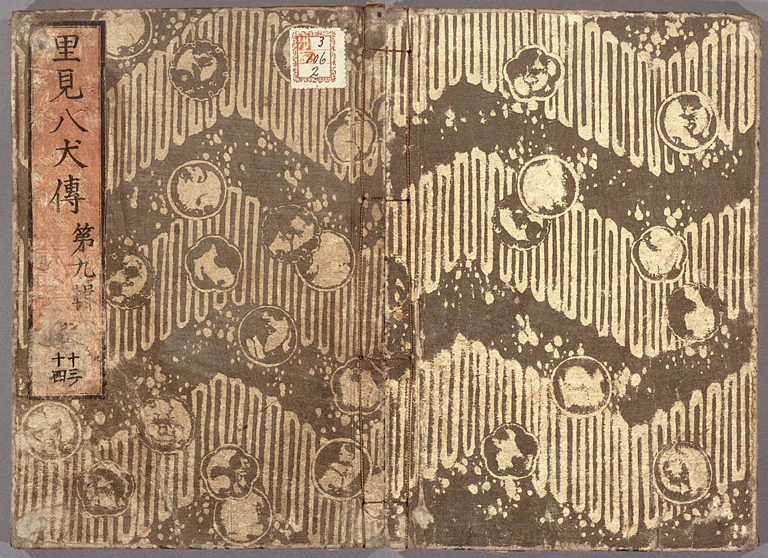

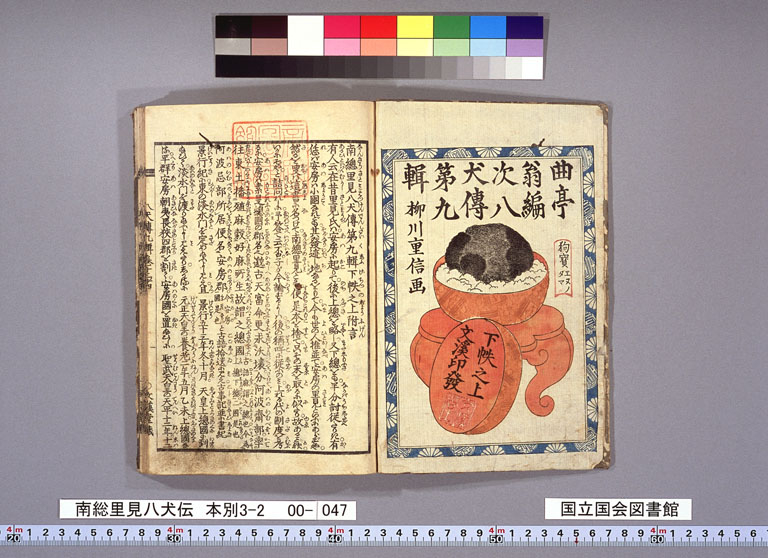

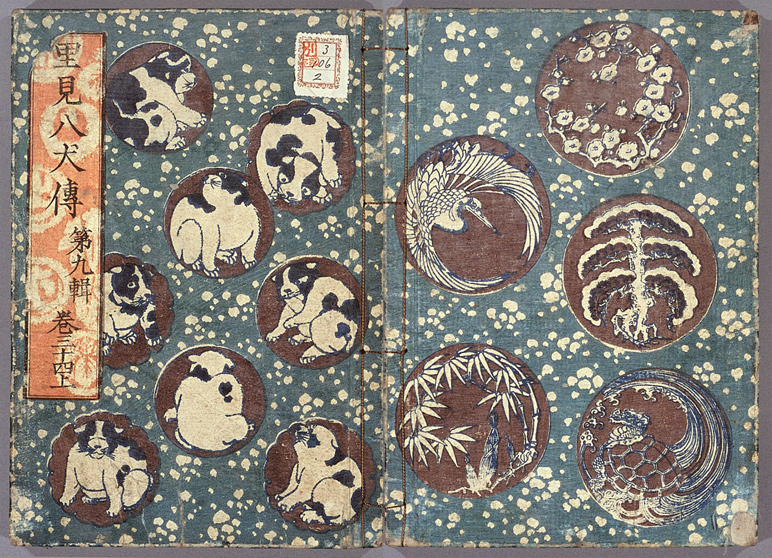

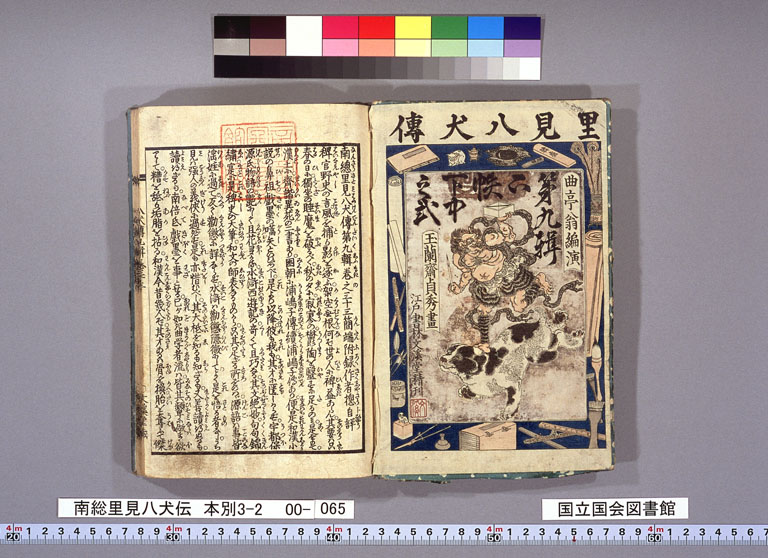

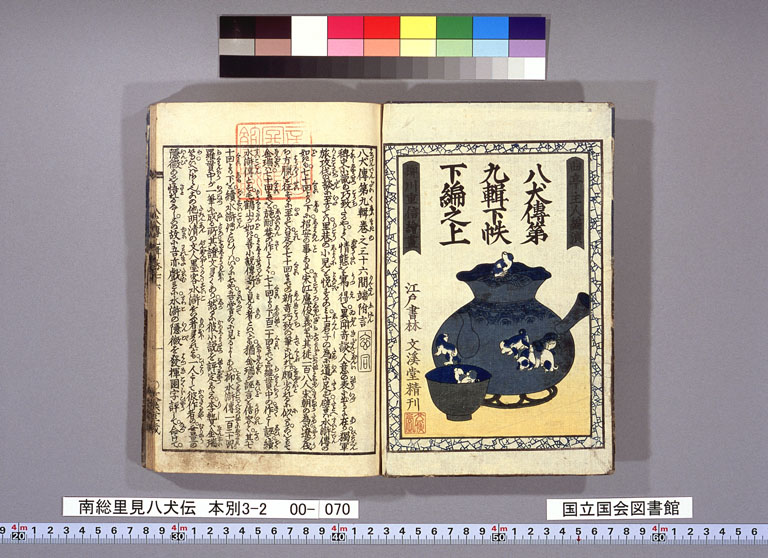

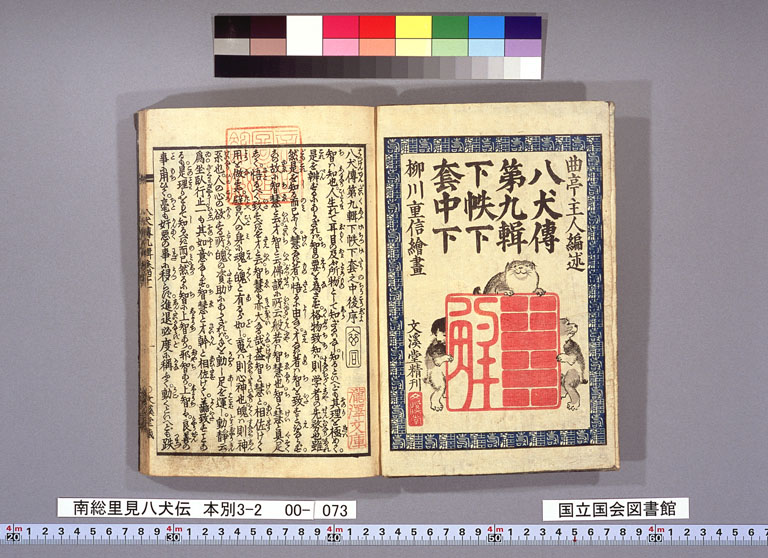

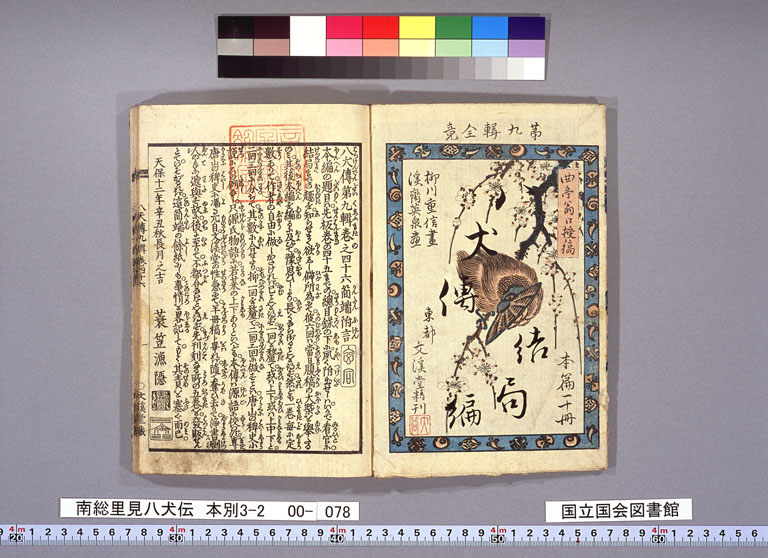

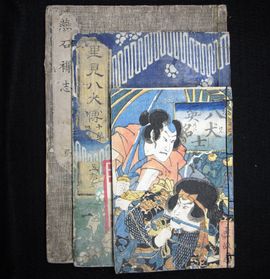

次に御覧に入れるのは、曲亭馬琴(滝沢+馬琴は間違い)の代表作『南総里見八犬伝』(全九集、文化十一〈1814〉年〜天保十三〈1842〉年)の初板初摺本です。十九世紀に入ると読本には大変にきれいな装飾が施されるようになります。これは、読本が貸本屋を通じて大衆化し商品価値を持つに至ったことを意味します。美しいデザインの表紙を御覧下さい。

Next I would like to introduce a copy of a first printing of the first edition of Kyokutei Bakin's great work the Nansou Satomi Hakkenden which was published between 1814 and 1842. You will see that once we reach the nineteenth century, yomihon come to be decorated in quite beautiful ways. This is because yomihon have come by this time to hold a mass commercial value through the role of commercial lending libraries. Please take a look at the design of the covers which are quite artistic.

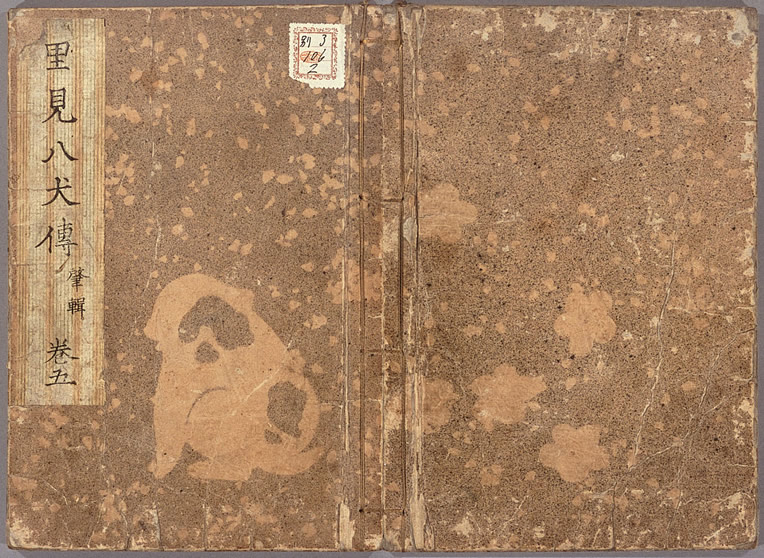

04.肇輯(初集)全五冊(大体、毎年五冊ずつ出板されました。)

First installment of five volumes (usually, five volumes were published every year).

05-01.初集の表紙と後ろ表紙(裏表紙)を並べると、絵柄が続きます。

When you line up the front and back covers of the first installment, it forms a pattern

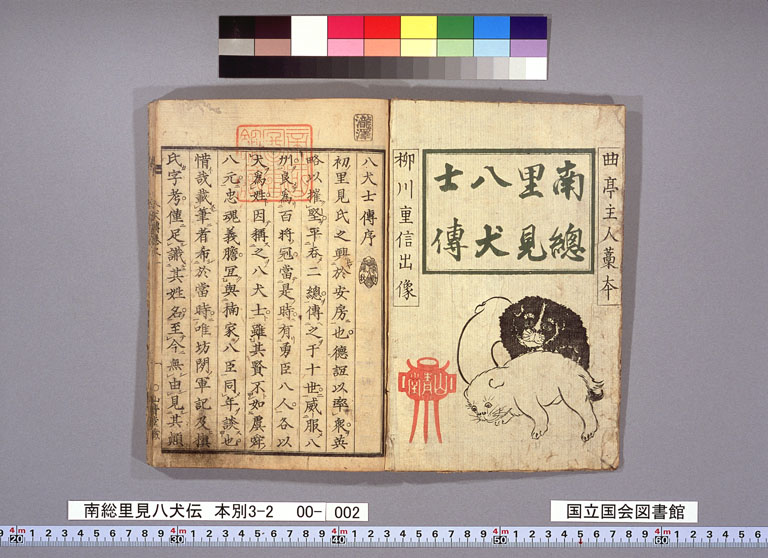

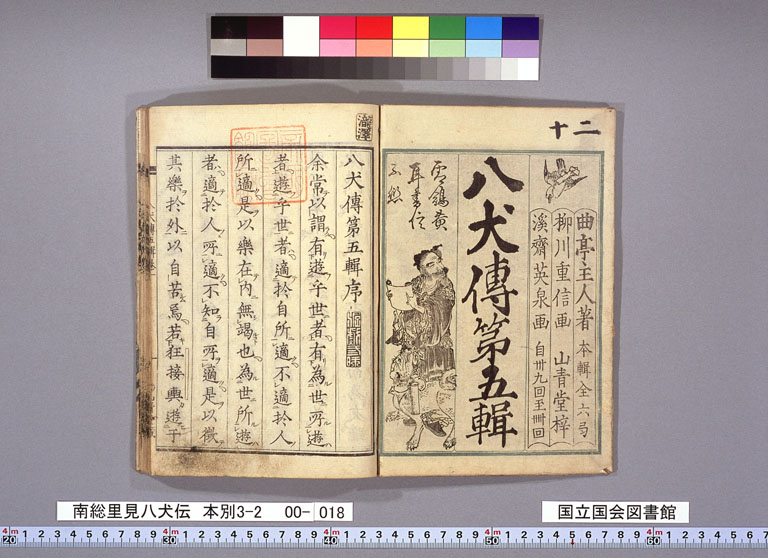

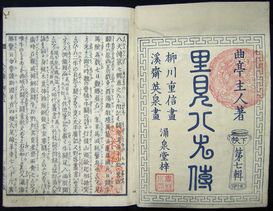

05-01a.初集の見返(表紙の裏側)と漢文序。「瀧澤」印、馬琴が持っていた本。国立国会図書館所蔵。

The Mikaeshi or title page of the first volume and the kanbun preface. Here you can see a seal that reads “Takizawa” marking this as Bakin's own copy. It's held at the National Diet Library in Tokyo.

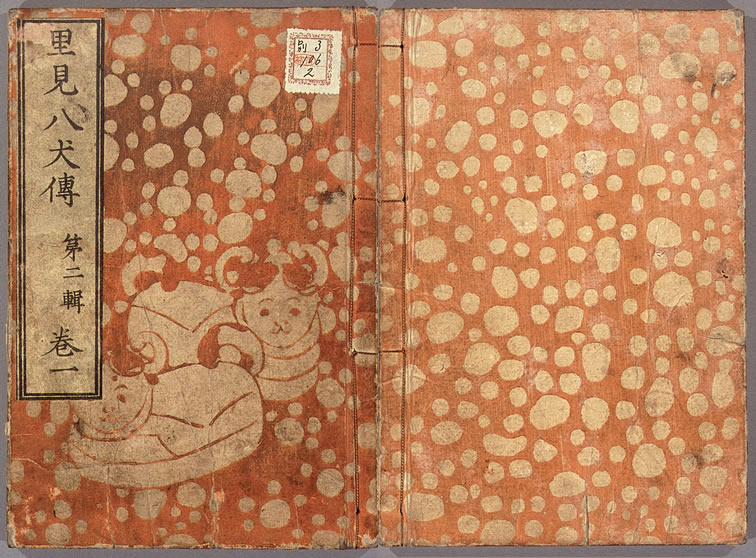

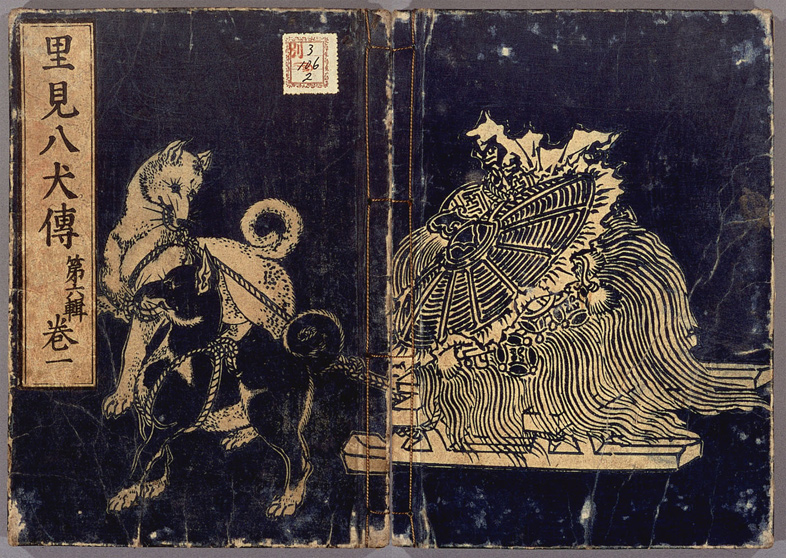

05-02.二輯(集)の表紙

Cover of a volume from the second installment

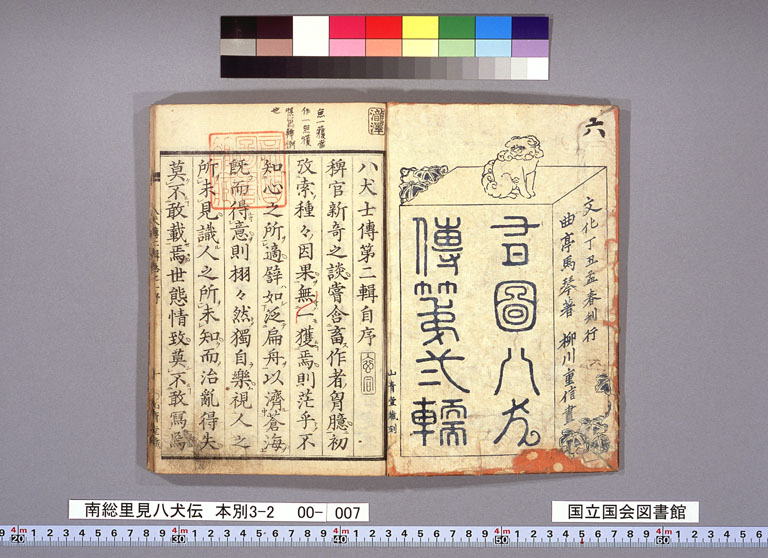

05-02a.二集の見返(ハンコの意匠)と序文(上に馬琴自筆の訂正が書き込まれている)

A title page and preface from a volume of the second installment. The title page is written in a script resembling a seal or hanko and on the title page you can see Bakins own marginal notes above the text.

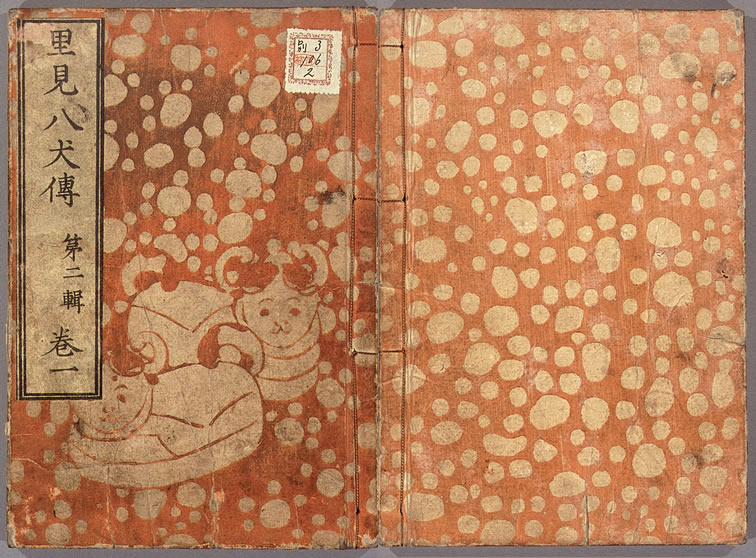

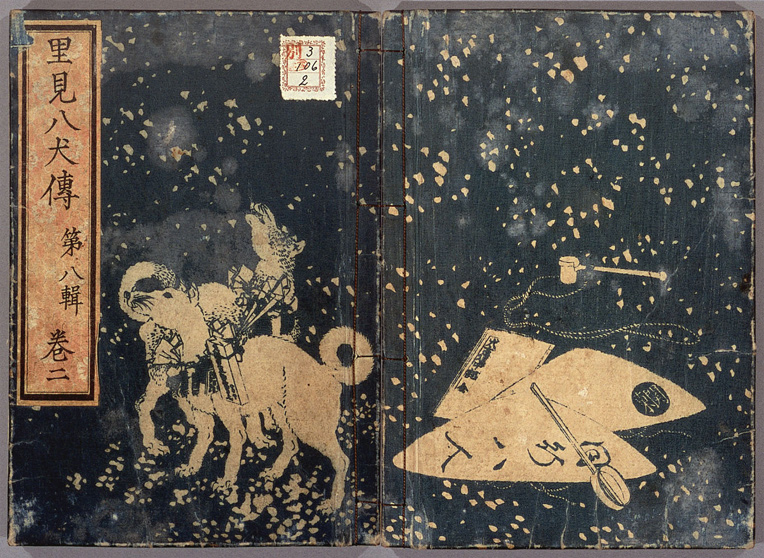

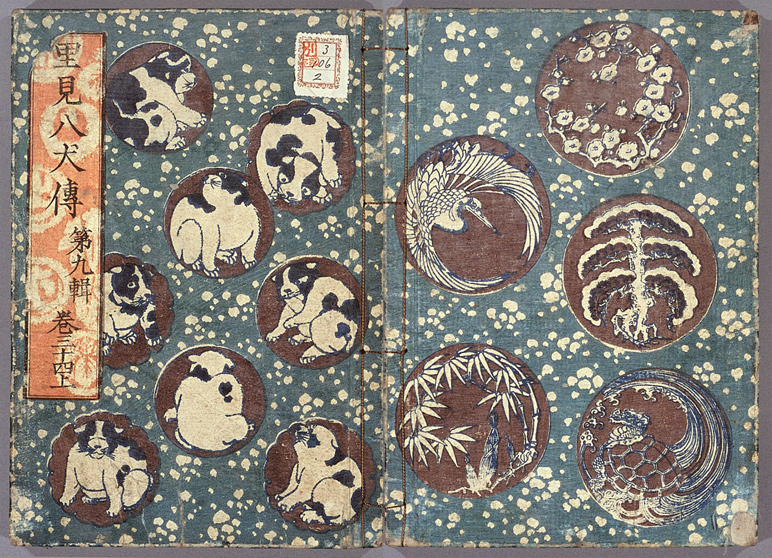

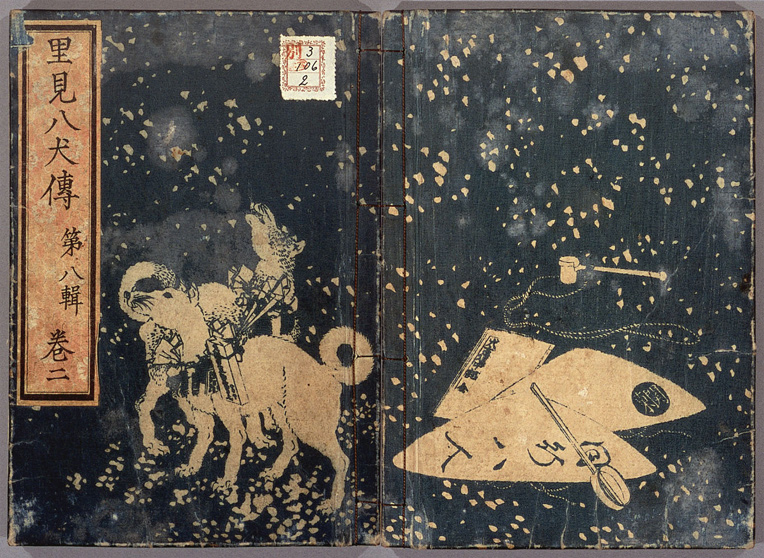

05-03.三集の表紙(小犬と沫雪の意匠)

Cover of a volume from the third installment with a design of puppies and snowflakes.

05-03a.三集の見返と序文

A title page and preface from a volume of the third installment.

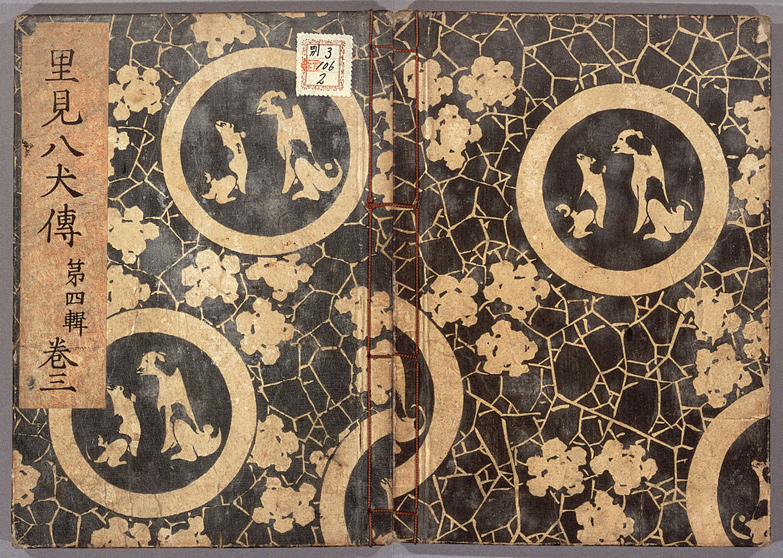

05-04.四集の表紙(梅花氷裂という意匠に二匹の犬で「八」という漢字。)

Cover from a volume of the fourth installment. The two dogs on the background of a pattern know as Baika Hyouretsu form the character for eight.

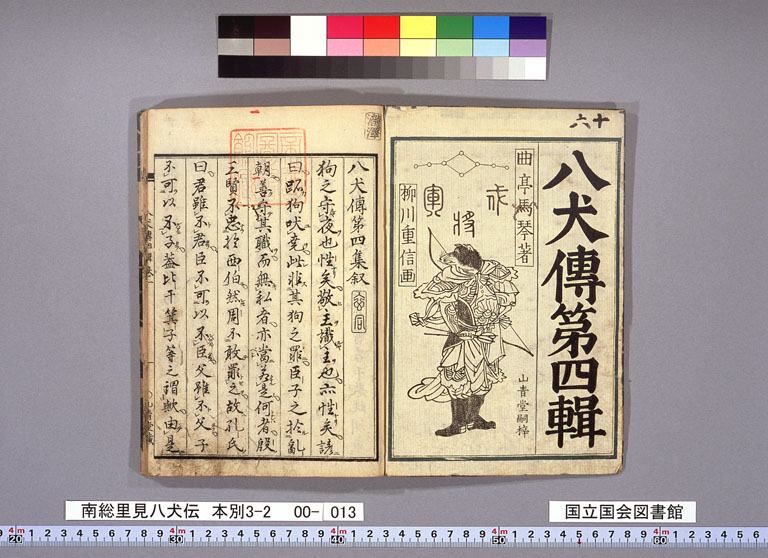

05-04a.四集の見返と序文

A title page and preface from a volume of the fourth installment.

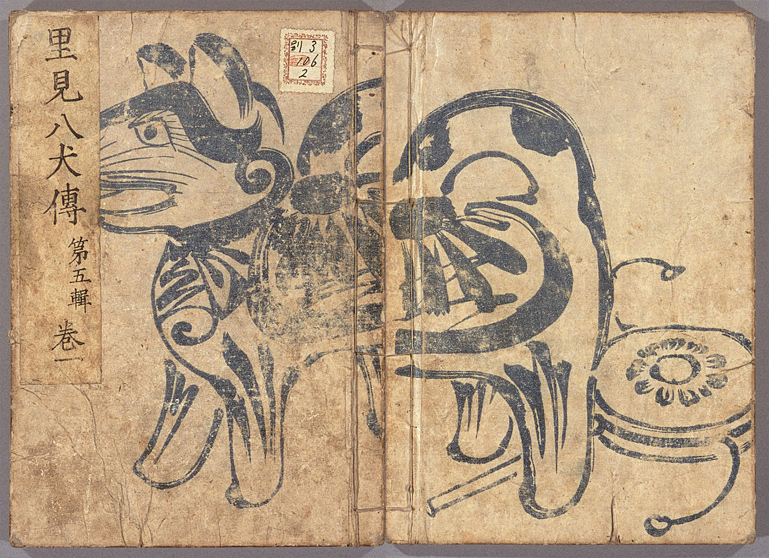

05-05.五集の表紙(狗張子とデンデン太鼓〈玩具〉)

The cover from a volume of the fifth installment. The cover shows two toys, and Inu Hariko and a DenDen Taiko.

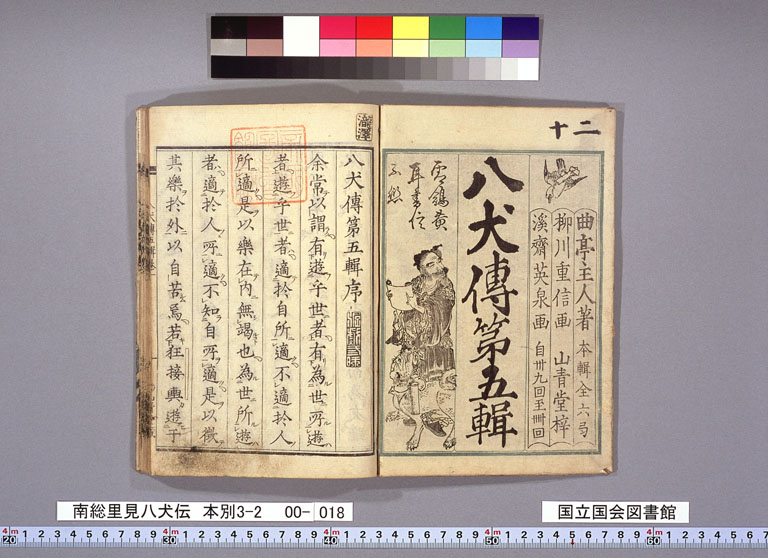

05-05a.五集の見返(伝書鳩と伝書犬「黄耳」)と序文

A title page and preface from a volume of the fifth installment. The title page shows a messenger pigeon and a messager dog.

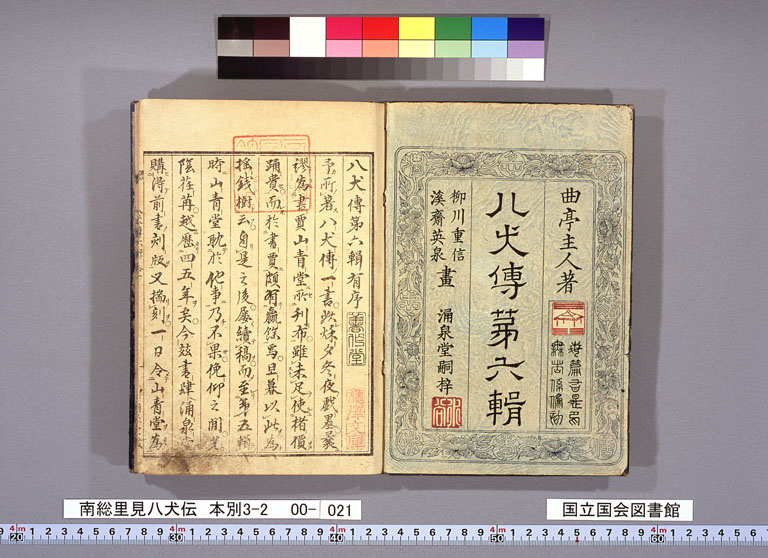

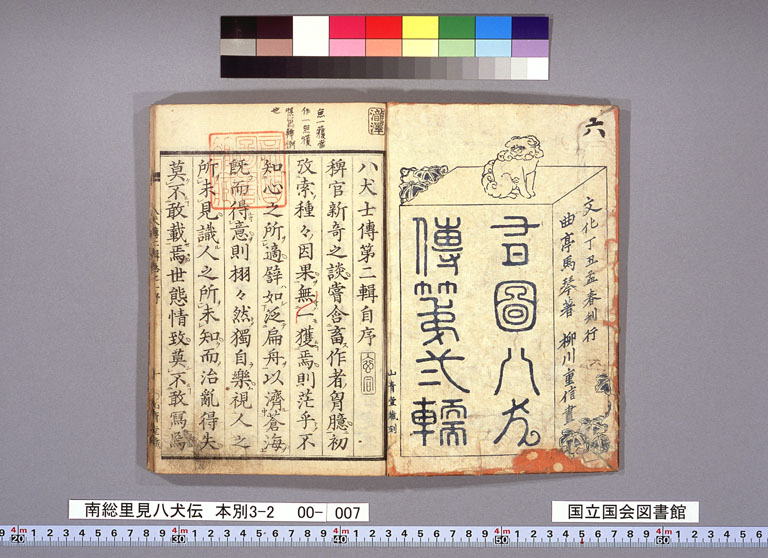

05-06.六集の表紙(「犬ゾリ」に宝づくし)

Cover of a volume from the sixth installment. The title page shows a Takarazukushi in a dogsled.

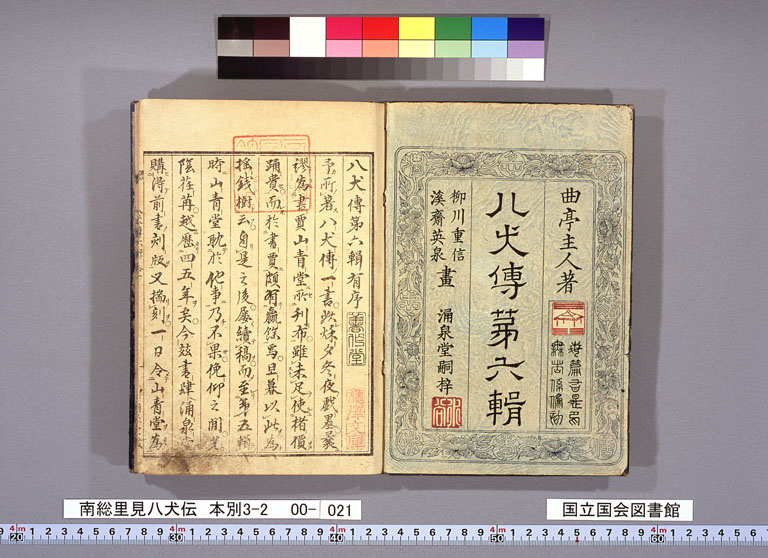

05-06a.六集の見返と序文(「瀧澤文庫」印〈馬琴の蔵書印〉)

A title page and preface from a volume of the sixth installment. This volume was part of Bakin's personal library and bears a seal reading “Takizawa bunko”.

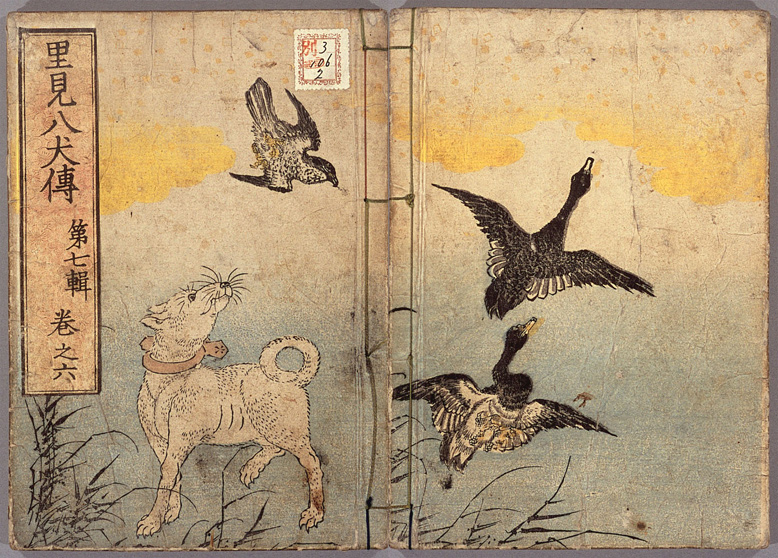

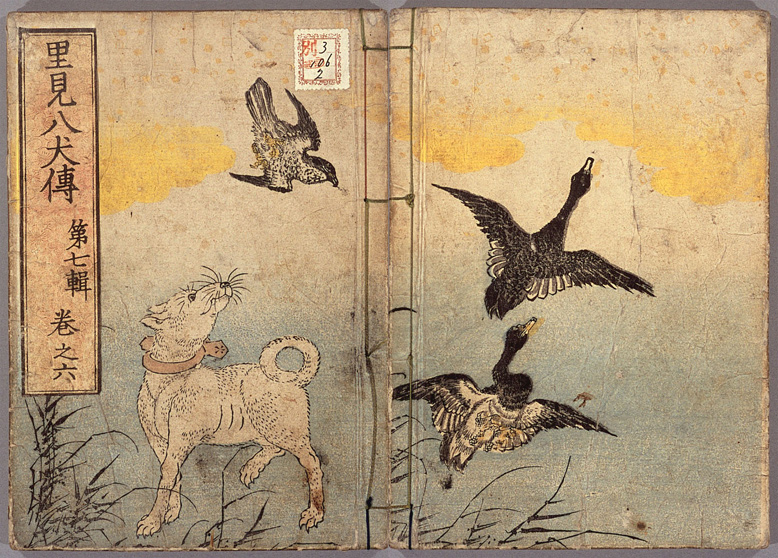

05-07.七集の表紙(雁と犬と鳩〈手紙を運ぶ動物たち〉)

The cover of a volume from the seventh installment bearing images of a wild goose, a dog, and a pigeon - animals used as mesengers.

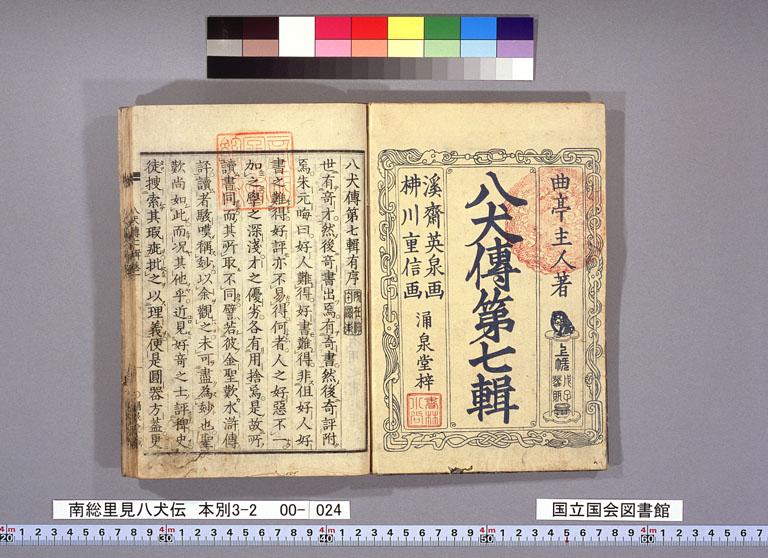

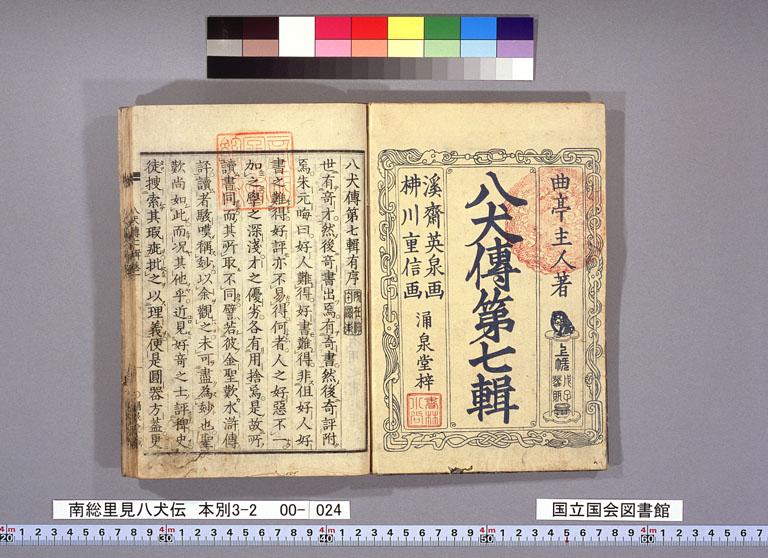

05-07a.七集上帙の見返と序文(七集は上下に分けた)

A title page and preface from a volume of the first part of the seventh installment (the seventh installment came out in two parts).

05-07b.七集下帙の見返と序文

A title page and preface from a volume of the second part of the seventh installment.

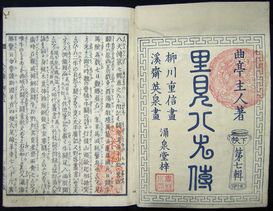

05-08.八集の表紙(伊勢参りの犬〈お札を首に付けている〉)

Cover from the eighth installment (a dog on the Ise pilgimage with a fuda attached around its neck).

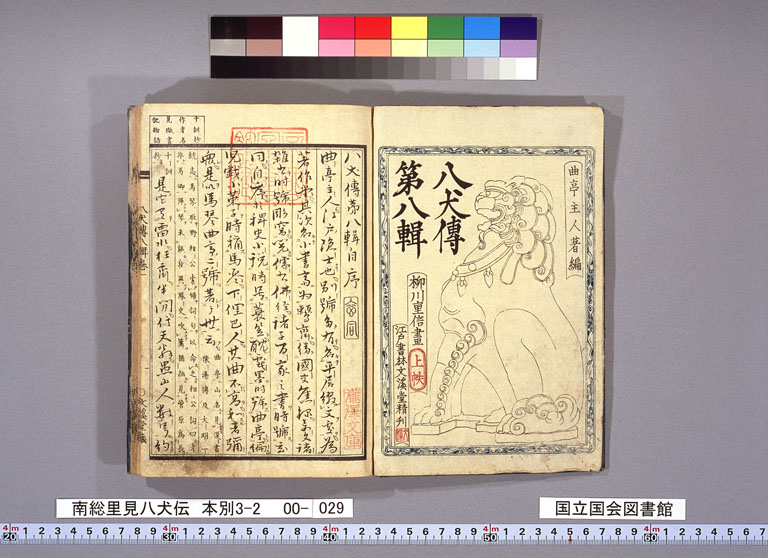

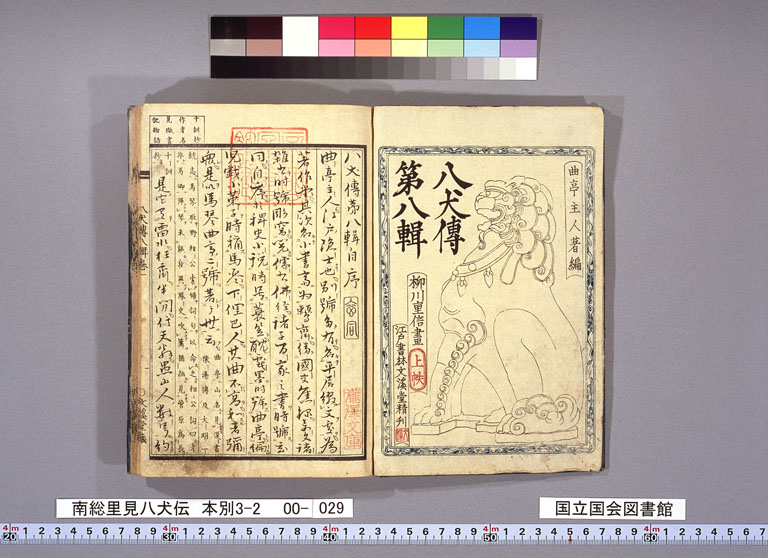

05-08a.八集上帙の見返と序文(八集も上下に分けた)

A title page and preface from a volume of the first part of the eighth installment (the eighth installment also came out in two parts).

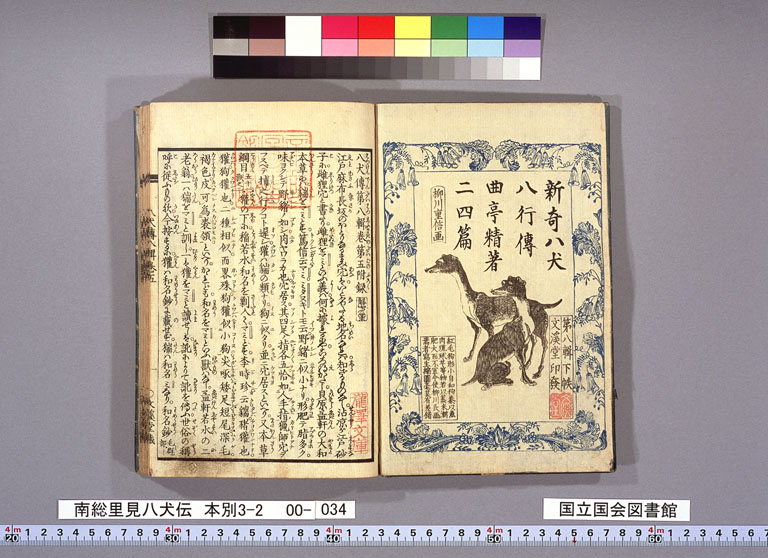

05-08b.八集下帙の見返と序文

A title page and preface from a volume of the second part of the eighth installment.

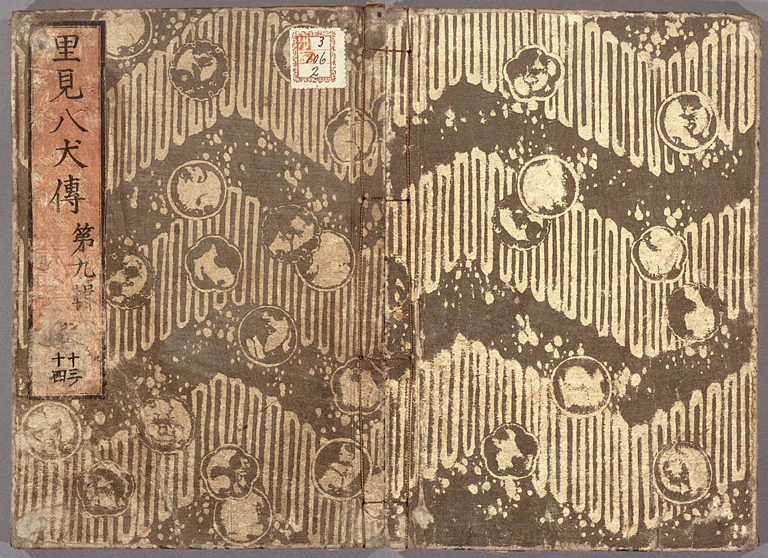

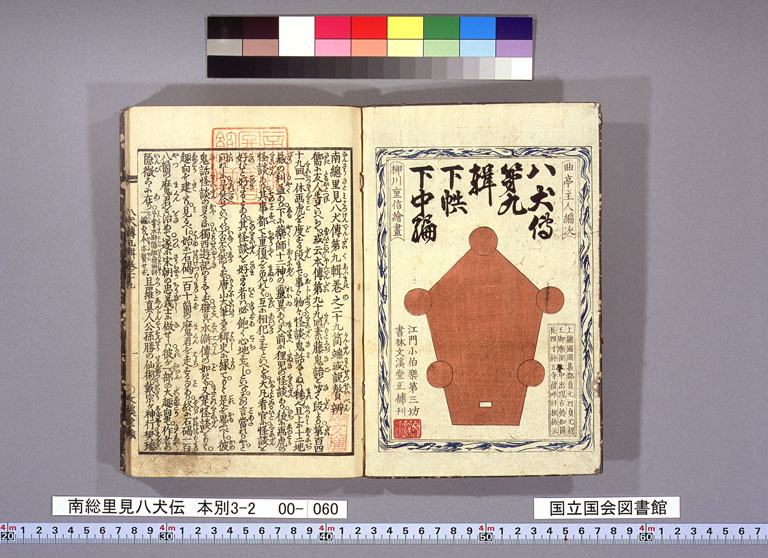

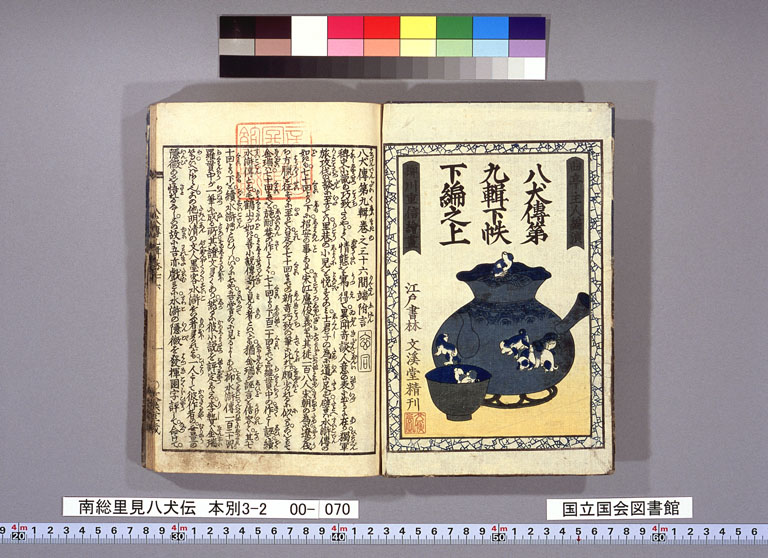

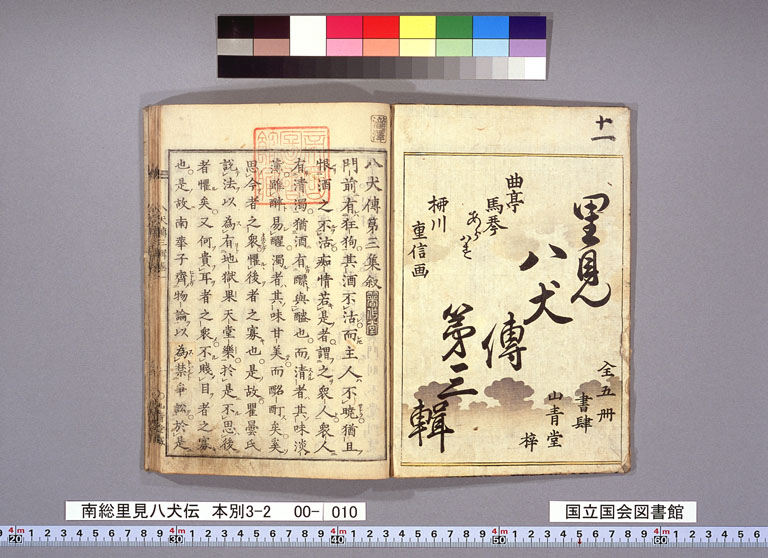

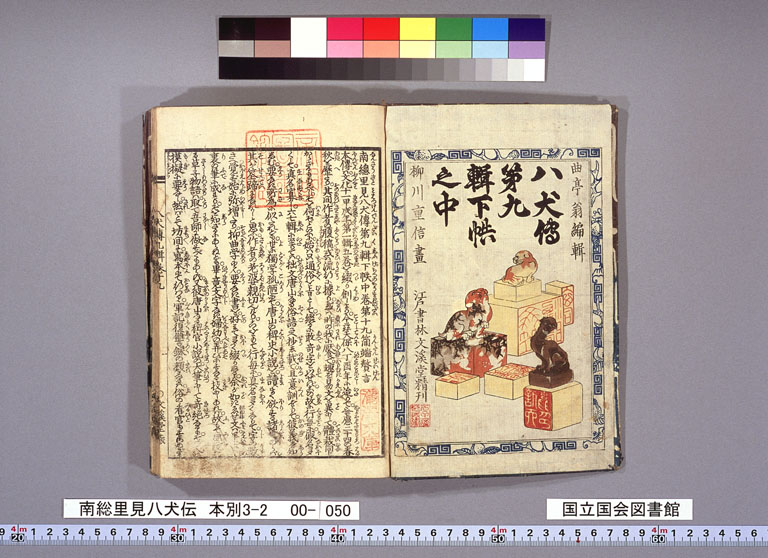

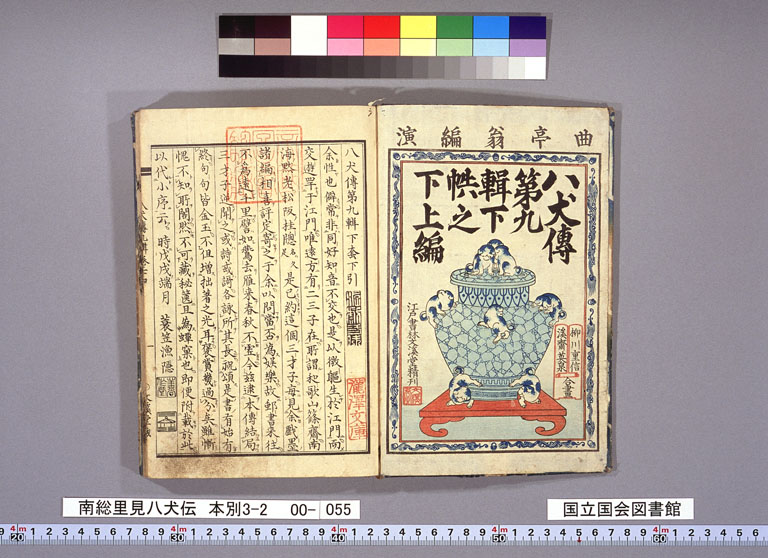

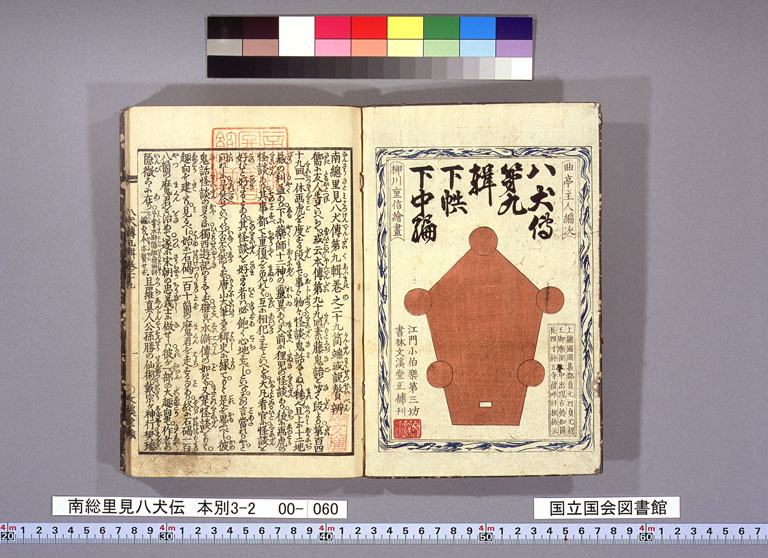

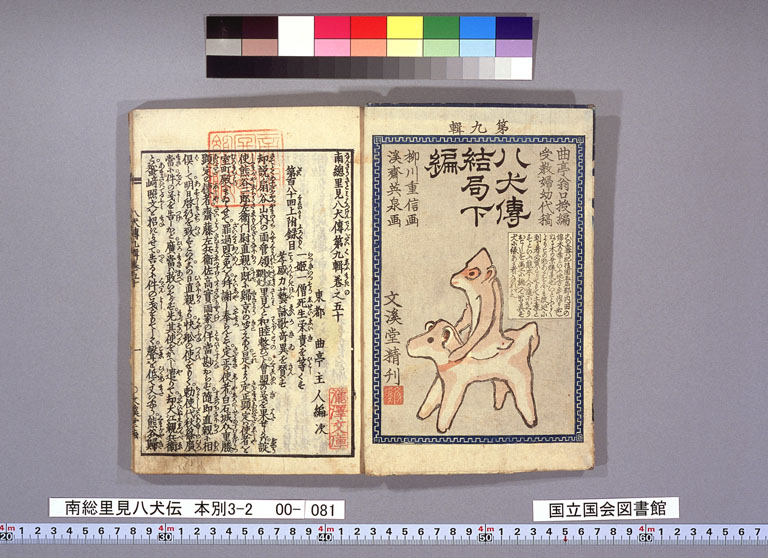

05-09.九集の表紙(以下「九集」で終わらせるために「九集」が延々と続き『八犬伝』の半分に及ぶ)

The cover of a volume from the ninth installment - in order to end in nine installments, the ninth installment went on and on and actually accounts for about half of the total Hakkenden.

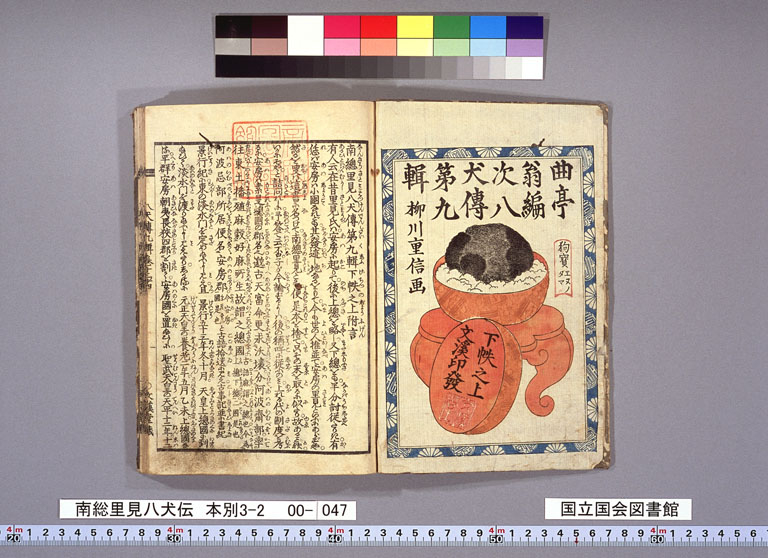

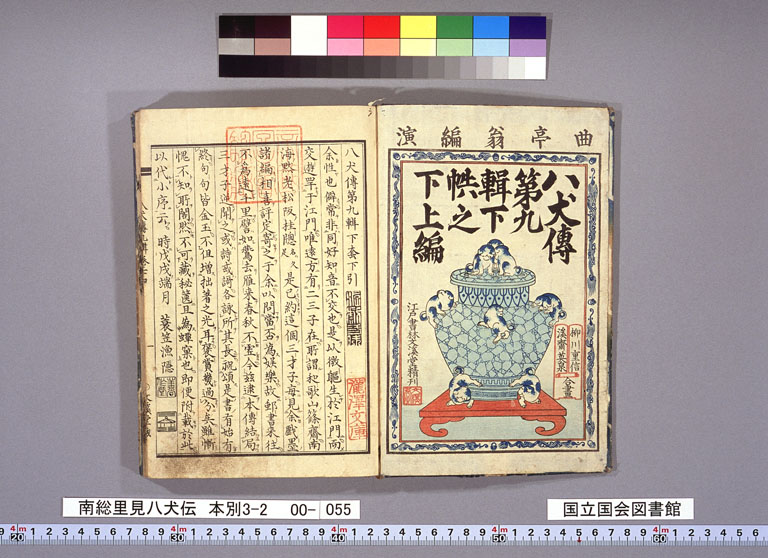

05-09a.九集の見返・序文

The cover, title page, and preface from a volume of the ninth installment.

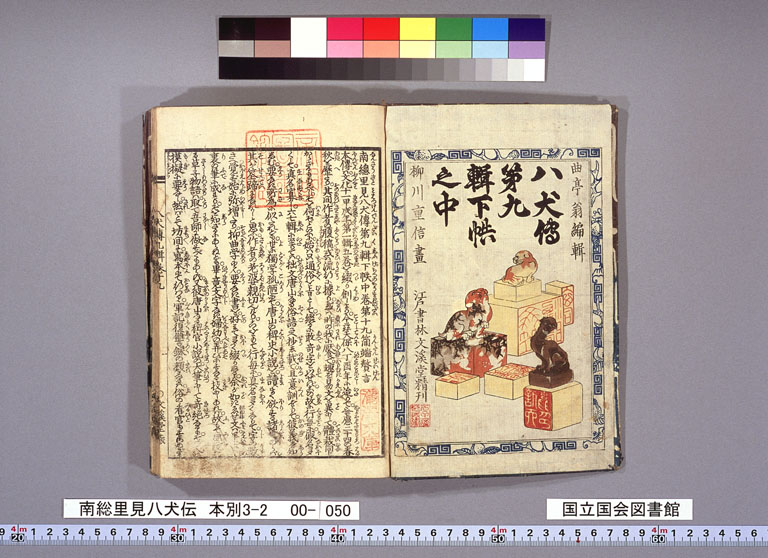

05-09b-c.以下、九集の表紙は同じ意匠で色違いが続く。

Below you can see that the same pattern with different colors continues.

05-09d-e.

05-09f-g.

05-09h-i.

05-09j-k.以下の二つも同じ意匠の色違い

The following are also of the same pattern but with different colors.

05-09l.

05-09m.見返に「《犬に乗った!》魁星(文運を主る星)」。魁星印は書物の巻頭に良く描かれた

On the Mikaeshi is the figure of Kaisei riding a dog. You often see of Kaisei at the opening of books.

05-09n-o.

05-09p.表紙(鶴亀と島台…めでたいもの=終わりが近い)

Cover bearing images of a crane, a turtle, and a shimadai all symbols of celebration marking that the end of the book is approaching.

05-09q.見返

05-09r.表紙(宝づくし…めでたいもの=終わりが近い)

A takarazukushi similarly pointing to the end being near.

05-09s.見返(「曲亭翁口授稿」とあり口述筆記をしたと明示する)

The title page which bears the words “dictated by Kyokutei okina” poiting to this portion have been dictated due to Bakin's failing eyesight.

05-09t.表紙(最終巻)

05-09u.見返(「曲亭翁口授編\受教婦幼代稿」とあり、馬琴の息子の嫁である「路(みち)」が口述筆記をしたと明示する)

Title page which bears the words “dictated by Kyokutei okina and transcribed by the wife of his son” pointing to this being transcribed by Bakin's daughter in law O'Michi.

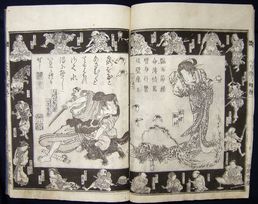

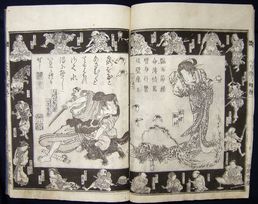

0006-7. 第六集の口絵(薄墨と艶墨との重ね刷り)

The frontispiece to a volume from the sixth installment printed with an overlaying of thin grayish ink and a thick lustrous ink know as tsuyazumi.

今ご覧頂いたのは『南総里見八犬伝』全一〇六冊の表紙と見返ですが、最後の二枚のように口絵や挿絵にも重ね刷が施されていて、手に取って読む気にさせる大変に美しい本です。

What I have shown here are examples taken from the 106 volumes of the Hakkenden published over 28 years during the first half of the 19th century.

As you can see from the final examples, the book contained color illustrations and frontispieces produced using the multistep printing technique many of you are familiar with from the history of ukuyo prints in order to produce an aesthetic which invited the reader to pick up the book and begin reading.

今回はこれ以上深入りしませんが、日本近世期の板本はその大部分が絵入りである点に特徴があります。ご承知の通り、ホノルル・アカデミー・オブ・アーツにも多くの美しい錦絵や絵入板本が所蔵されていますが、テキストとイメージの不可分な関連という日本の本の伝統は、マンガ文化とも深いところで連続しているものと考えられます。

I do not have time to go into much detail today but one of the defining characteristics of the block printed book in early modern Japan was that most included illustrations. The Honolulu Academy of Arts itself is home to many woodblock prints and illustrated books, you know. It's even possible to imagine that this close connection between word and image in Japanese book culture has some kind of deep connection with the culture of modern Manga.

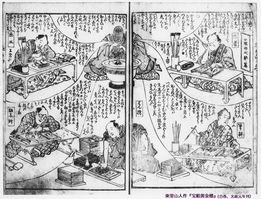

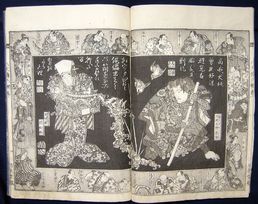

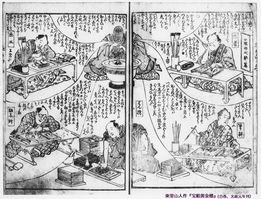

さて、次に十九世紀の江戸における出板の様子が描かれた草双紙の挿絵を紹介しましょう。東里山人作の合巻『宝舩黄金檣(たからぶねこがねのほばしら)』(春扇画、文政元〈1818〉年、和泉屋市兵衛板)です。

Now I would like to introduce an image from an illustrated work of fiction which depicts the state of publishing in the nineteenth century. It is taken from a work entitled Takarabune Kogane Hashira published in 1818 by Touri Sanjin.

10.「金銀のために使われて、人々身を苦しめるところの絵組」と題するページ。

ここに出したページは、本作の筋には余り関係ないのですが、19世紀の板本の制作過程が描かれていて興味深いものです。

The page I've given here does not have much to do with the plot of the book but it is quite interesting because it depicts the process of putting together a block printed book in the 19th century.

中心に座っていて、顔が小判になっているのは板元(出板者)の和泉屋市兵衛です。

正月の出板に間に合うように「急いで仕事をしろ」と職人達を急かしています。

The figure in the center - whose face is covered over with a coin - is the publisher, Izumi Ichibee. He's putting pressure on the various workers in the illustration to hurry up to so he can publish in time for the new year.

右側の団子鼻が作者の東里山人で、作品の構想を考えているところです。前に広げた〈稿本〉に、本文テキストと挿絵の下絵を描いて画工と筆耕に回します。

On the right hand side is the figure of the author, Touri Sanjin thining up the work. On the paper in front of him he is writing the text and sketching the illustrations which he will then pass on to the copyist and the illustrator.

左側が画工(浮世絵師)の勝川春扇です。作者から回わってきた〈稿本〉に基づいて挿絵を薄い和紙に清書して〈版下〉を作成します。浮世絵師にとって一枚摺の錦絵(多色刷の浮世絵)を描くのと同様に、絵入り板本の挿絵を描くことも仕事(収入源)の一つだったのです。

On the left is the illustrator, the ukiyoe print designer Katsukawa Shunsen. He is producing illustrations based on the author's sketches on very thin Japanese paper that will then be used as the basis for the carved blocks. For ukiyoe print designers, drawing illustrations for printed books was a form of work and a source of income just like creating designs for ukiyo-e.

注意すべき点は、作者のラフスケッチに基づき、全体の構図も細かい持ち物なども、すべて作者の指示に従って描いていると言う点です。近世期には、画工が勝手に小説の挿絵を描くことは、ほとんど無かったと言って良いと思います。

One point worth noticing is that everything from the overall composition down to details such as various objects in the illustration are all based on the author's rough sketch and everything is drawn according to the author's instructions. During the early modern period there are virtually no instances of an illustrator making images for a work of fiction of his own accord.

右下は筆耕です。画工が描いた挿絵の余白部分に、作者の原稿に基づいて、レイアウトを考慮しながら本文テキストを清書し〈版下〉を完成します。

On the bottom right is the copyist. He writes out the author's text in the blank spaces left by the illustrator while taking account of layout.

左下は板木師(彫師)です。画工と筆耕が仕上げた〈版下〉を〈板木〉に裏返しに貼り付けて写し取り、印刷されない部分を彫刻刀で彫ります。ちょうどスタンプのように仕上げるのです。大変に細かい作業なので、長年修行して技術を身につけた職人が担当します。〈彫師〉の姿を描いた絵を見ると、眼鏡をかけている人が多いので、目が悪くなる人が多かったようです。

On the lower left is the carver. He pastes onto the block the manuscript he has received containing the text of the copyist and the images - with text and image facing downwards - and then carves out those parts of the block which will not be printed, leaving elevated the surfaces of the text and illustrations. It functions just like a stamp. This is extremely detailed work and so it is done by a journeyman who has spent a longtime mastering the skills. In many illustrations that depict block carvers, the carver is wearing glasses and one suspects that the demanding work caused many carvers to have failing eyesight.

中央の下は「はん摺」(摺師)です。板木に墨を塗り、和紙を乗せて上からバレンで擦って印刷します。とても腕力が必要な作業で、逞しい腕をしています。また、畳に座って作業をするので、力が入れやすいように、少し手前が持ち上がった台の上で作業をしているのが分ります。左右に刷り上がったものが積み上げられています。

At the center bottom is the printer. He inks the printing block and then prints the pages through laying it on paper and then rubbing it with a tool called a baren. It is work that required a great deal of strength in the arms and you can see in the illustration he is depicted with quite muscular arms. Also in order to make it easier for the printer who worked sitting on tatami, he worked on a printing board which was slightly elevated at the front to make it easier to push down on. To the right and left of him you can see already printed pages stacked up.

板元の家内制手工業(マニフアクチャー)とでも言える様子が良く分かりますね。

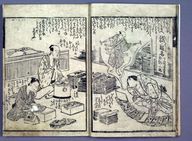

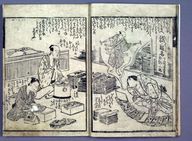

このようにして刷り上がった紙を半分に折り、ベージ順に並べ、表紙を付けて糸で綴るのです。この様子は、十返舎一九作画『的中地本問屋(あたりやしたじほんといや)』(享和二〈1802〉年刊、村田屋治郎兵衛板)という出板業界の裏側を描いた黄表紙に出て来ます。

I think we can get a good idea from this of what the manufacture of a block printed book looked like. From here, the printed pages would be folded in half and arranged in order and a cover would be attached with thread. This can be see in an 1802 work by Jippensha Ikku , Atariyashita Jihon Toiya, which portrays the behind the scenes of the publishing world.

10a.左側の少年が三角形の道具を使って半分に折っています。右側の男性は、それをベージ順に並べています。

On the left, a youth is using a triangle shaped tool to fold the pages in half. On the right an man is putting the pages in order.

10b.左側の女性達が糸と針を使って四つ目綴にしています。

On the left here you can see a group of women using needles and thread to create a binding style known as Yotsumetoji.

10c.完成した本。固い内容の本は〈大本〉、普通の本は〈半紙本〉、大衆小説は〈中本〉とジャンルによって大きさが決まっていました。『八犬伝』は半紙本、草双紙は中本です。

A completed book. The size of the book was dictated by its contents with serious books published in large oohon format, normal books published in mid hanshibon format and popular works of fiction published in somewhat smaller chuubon format. The Hakkenden which I mentioned earlier was a hanshibon; illustrated fiction known as kusazoushi were chuubon.

日本の和本は大きさにかかわらず、基本的に四つの穴をあけて綴られています。和本は原則として縦書きですから右から左に開けて読み進めます。

Regardless of the size of the format, Japanese books were generally bound by making four apertures. As a rule, Japanese books are written vertically, one reads from right to left.

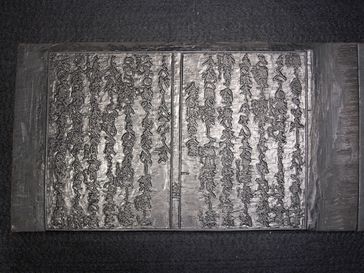

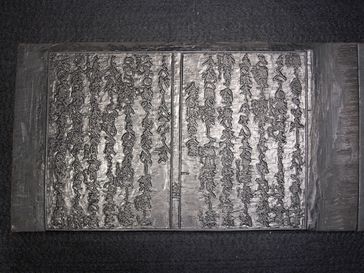

ついでに、手許にある〈板木〉の写真を御覧に入れましょう。

Next please take a look at an example of a printing block which I happen to have.

0011.板木(小型の銭相場の本のようです)

Printing block

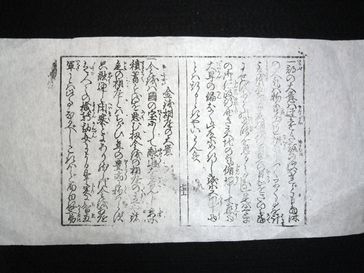

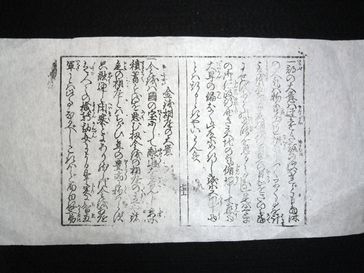

0012.試しに摺ってみたもの。なかなか上手く摺るのは難しい。

Here is an example of an attempt I made to print off it. It is pretty difficult to make a good print off one of these blocks.

以上、見てきたように板元がプロデューサーとして多くの職人や家内の者を動員して本を作っていたのです。そして、作者や画工も本作りを担う職人の一部として考えるべきだと思います。本を出板するためには先行投資が必要であり、実際に売り出してみないと儲かるかどうか分りません。つまり、出板とは、きわめてギャンブル性の強い商売なのです。そして、そのリスクを負っているのは、作者や画工ではなくて、板元なのです。このことは現在でも本質的に変わっていません。

As we have seen so far, the publisher was a kind of producer who mobilized a great number of workmen and family members to produce a book. And I believe we can think of both author and illustrator as themselves workmen who were responsible for one part of this process. To publish a book advance capital was necessary and one did not know if the book would be profitable until it was sold. In other words, publishing is a very risky business. And the one who bore that risk was not the author or illustrator but the publisher. This is not really any different today.

つまり、作者や画工が書きたい本を書きたいように出版できた時代など存在しないかった。言い換えれば、出版業という業界の中で、板元のプロデュースがあることによって、はじめて作者も才能が発揮できたと考えるべきなのです。もちろん、作者の才能や独自性は否定しませんが、出板のイニシアチブが板元にあったことは確認しておく必要があるのです。

In other words, the there has never been a period in history where the author or illustrator was able to do his or her work just as they pleased and have it published. Or to put it a different way, we should perhaps imagine that within the publishing world it is by precisely means of the publisher's role as producer that the author was able to display his or her genius. I am not, of course, denying the problem of genius or originality of the author but think that we need to recognize that the initiative for publishing lay with the publisher.

以上、駆け足でお話ししてきましたが、十九世紀の日本における出板の様子がお分かり頂ければ幸いです。

なにかご質問があれば、ご遠慮なくお申し出下さい。ご清聴ありがとうございました。

I am afraid I have covered a lot of ground rather quickly but I hope you have learned something of the state of publishing in nineteenth-century Japan. If you have any questions please do not hesitate to ask.

Thank you for your patience.

# Bookmakers and the Publishing Systems of Nineteenth-Century Japanese Fiction

# 造本から見る江戸読本の出板システムについて(邦文付き発表原稿)

# AAS(Association for Asian Studies) annual conference 2011 in Honolulu

# Session 194. The Printed Book as a Physical Object in Early Modern Japan, 1600-1900

# セッション194. 日本近世期(17〜19世紀)におけるモノとしての〈板本〉

# 2011/03/31

# Copyright (C) 2021 TAKAGI, Gen

# この文書を、フリーソフトウェア財団発行の GNUフリー文書利用許諾契約書ヴァー

# ジョン1.3(もしくはそれ以降)が定める条件の下で複製、頒布、あるいは改変する

# ことを許可する。変更不可部分、及び、表・裏表紙テキストは指定しない。この利

# 用許諾契約書の複製物は「GNU フリー文書利用許諾契約書」という章に含まれる。

# 高木 元 tgen@fumikura.net

# Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of

# the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the

# Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-

# Cover Texts.

# A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License".